Lee Scratch Perry Lives In Switzerland

Jun 03, 2011 Q&A: Lee 'Scratch' Perry Rosanna Greenstreet 'The last time I had a spliff it knocked me out for a day, a night and another day'. He is married for the second time, and lives in Switzerland. Lee Scratch Perry OfficialT-ShirtsSocksPostersArtMusic. 1 Applies to shipping within Switzerland. Information about shipping policies for other countries can.

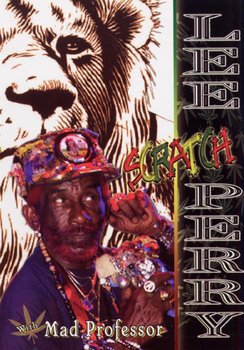

Dec 05, 2015 Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s Secret Laboratory Studio Burns Down “Maybe I have to make a change in my life, and put away the candle-burning for a while and clean up my brain,” dub legend says. Feb 06, 2009 The definitive life story about Jamaican musical legend Lee 'Scratch' Perry. Showtimes & Tickets Showtimes & Tickets Top Rated Movies Most Popular Movies Browse Movies by Genre Top Box Office In Theaters Coming Soon Coming Soon DVD & Blu-ray Releases Release Calendar Movie News India Movie Spotlight. When you consider Jamaican record producer Lee 'Scratch' Perry is still taking to stages globally at the age of 78, you may be encouraged to pick up an acoustic and see if it makes you feel any younger. Of course it is not the actual act of performing that keeps Lee playing live, it is the passion for the music that is so visible. About Lee “Scratch” Perry Lee “Scratch” Perry OD (b. 1936 in Kendal, Jamaica) lives and works between Einsiedeln, Switzerland and Negril, Jamaica. He has worked with artists including Bob Marley and the Wailers, Junior Murvin, the Beastie Boys, and The Clash, among many others, and was awarded a Grammy for Best Reggae Album in 2003.

Artist Biography by John Dougan

A notoriously eccentric figure whose storied reputation and colorful personality match the sheer strangeness of much of his recorded output, Lee Perry is unquestionably one of reggae's most innovative, influential artists. His mixing-board innovations, from his early use of samples to hallucinatory echo and reverb effects, set the stage for generations of musical experimentation, particularly throughout electronic music and alternative/post-punk, and his free-association vocal style is a clear precedent for rap. Active as a producer and vocalist since the early '60s, he helped guide Jamaican music's shift from ska and rocksteady to reggae with singles like 'People Funny Boy' (1968). During the '70s, he became a super-producer, helming seminal works by Bob Marley & the Wailers, the Congos, and Junior Murvin, in addition to releasing dub albums such as Upsetters 14 Dub Blackboard Jungle (1973) and Super Ape (1976), often credited to his band the Upsetters. His work became popular in the U.K., and he collaborated with the Clash, broadening his audience. By the end of the '80s, he had begun recording extensively with dub acolytes such as Mad Professor and Adrian Sherwood. Compilations such as 1997's Arkology and acknowledgment from alternative acts like the Beastie Boys confirmed Perry's legendary status during the '90s. He remained highly active during the first two decades of the 21st century, touring often and collaborating with artists ranging from Andrew W.K. (2008's Repentance) to the Orb (2012's The Orbserver in the Star House), in addition to revisiting earlier material on releases like 2017's Super Ape Returns to Conquer.

A notoriously eccentric figure whose storied reputation and colorful personality match the sheer strangeness of much of his recorded output, Lee Perry is unquestionably one of reggae's most innovative, influential artists. His mixing-board innovations, from his early use of samples to hallucinatory echo and reverb effects, set the stage for generations of musical experimentation, particularly throughout electronic music and alternative/post-punk, and his free-association vocal style is a clear precedent for rap. Active as a producer and vocalist since the early '60s, he helped guide Jamaican music's shift from ska and rocksteady to reggae with singles like 'People Funny Boy' (1968). During the '70s, he became a super-producer, helming seminal works by Bob Marley & the Wailers, the Congos, and Junior Murvin, in addition to releasing dub albums such as Upsetters 14 Dub Blackboard Jungle (1973) and Super Ape (1976), often credited to his band the Upsetters. His work became popular in the U.K., and he collaborated with the Clash, broadening his audience. By the end of the '80s, he had begun recording extensively with dub acolytes such as Mad Professor and Adrian Sherwood. Compilations such as 1997's Arkology and acknowledgment from alternative acts like the Beastie Boys confirmed Perry's legendary status during the '90s. He remained highly active during the first two decades of the 21st century, touring often and collaborating with artists ranging from Andrew W.K. (2008's Repentance) to the Orb (2012's The Orbserver in the Star House), in addition to revisiting earlier material on releases like 2017's Super Ape Returns to Conquer. Born in the rural Jamaican village of Kendal in 1936, Perry began his surrealistic musical odyssey in the late '50s, working with ska man Prince Buster selling records for Clement 'Coxsone' Dodd's Downbeat Sound System. Called 'Little' Perry because of his diminutive stature (he stands at 4'11'), he was soon producing and recording at the center of the Jamaican music industry, Studio One. After a falling out with Dodd (throughout his career, Perry has a tendency to burn his bridges after he stops working with someone), he went to work at Wirl Records with Joe Gibbs. Perry and Gibbs never really saw eye to eye on anything, and in 1968, Perry left to form his own label, called Upsetter. Not surprisingly, Perry's first release on the label was a single entitled 'People Funny Boy,' which was a direct attack upon Gibbs. What is important about the record is that, along with selling extremely well in Jamaica, it was the first Jamaican pop record to use the loping, lazy, bass-driven beat that would soon become identified as the reggae 'riddim' and signal the shift from the hyperkinetically upbeat ska to the pulsing, throbbing languor of 'roots' reggae.

From this point through the '70s, Perry released an astonishing amount of work under his name and numerous, extremely creative pseudonyms: Jah Lion, Pipecock Jakxon, Super Ape, the Upsetter, and his most famous nom de plume, Scratch. Many of the singles released during this period were significant Jamaican (and U.K.) hits, instrumental tracks like 'The Return of Django,' 'Clint Eastwood,' and 'The Vampire,' which cemented Perry's growing reputation as a major force in reggae music. Becoming more and more outrageous in his pronouncements and personal appearance (when it comes to clothing, only Sun Ra could hold a candle to Perry's thrift-store outfits), Perry and his remarkable house band, also named the Upsetters, worked with just about every performer in Jamaica. Mixmeister bpm analyzer para android. It was in the early '70s after hearing some of King Tubby's early dub experiments that Perry also became interested in this form of aural manipulation. He quickly released a mind-boggling number of dub releases and eventually, in a fit of creative independence, opened his own studio, Black Ark.

It was at Black Ark that Perry recorded and produced some of the early, seminal Bob Marley tracks. Using the Upsetters rhythm section of bassist Aston 'Familyman' Barrett and his drummer brother Carlton Barrett, Perry guided the Wailers through some of their finest moments, recording such powerful songs as 'Duppy Conqueror' and 'Small Axe.' The good times, however, didn't last, especially after Perry, unbeknownst to Marley and company, sold the tapes to Trojan Records and pocketed the cash. Island Records head Chris Blackwell quickly moved in and signed the Wailers to an exclusive contract, leaving Perry with virtually nothing. Perry accused Blackwell (a white Englishman) of cultural imperialism and Marley of being an accomplice. For years, Perry referred to Blackwell as a vampire, and accused Marley of having curried favor with politicians in order to make a fast buck. These setbacks did not stem the tide of Perry releases, be they of new material or one of a seemingly endless collection of anthologies. Perry was also expanding his range of influence, working with the Clash, who were huge Perry fans, having covered the Perry-produced version of Junior Murvin's classic 'Police and Thieves.' Perry was brought in to produce some tracks for the Clash, but the results were remixed more to the band's liking.

Lee Scratch Perry Songs

All this hard work was wreaking havoc with Perry's already fragile mental state, leading to a breakdown. The stories of his mental instability were exacerbated by tales of massive substance abuse (despite his public stance against all drugs except sacramental ganja), which reportedly included regular ingestion of cocaine and LSD; one potentially apocryphal story even had Perry drinking bottles of tape head-cleaning fluid. But these stories, as with much surrounding Perry, blur fact and fiction. One story that was true was that Black Ark, and everything in it, burned to the ground. Perry claims bad wiring was the culprit, but the more familiar and commonly accepted story is that Perry burned the studio down in a fit of acid-inspired madness, convinced that Satan had made Black Ark his home. Whatever the case, the site of Perry's greatest moments as a producer had been reduced to (and remained) a pile of rubble and ash. Soon after the fire that consumed Black Ark, Perry, increasingly fed up with the music business in Jamaica (which by all accounts is extremely corrupt), decided to leave the country.